Simply put, the book was far too gendered for my taste. I want to be cautious here, because I think this is an area in which feminists sometimes do more harm than good. They obsess over the representation of women in literature and cinema, and in doing so sometimes turn characters into gendered objects. In my ideal feminist world, female characters aren't considered good representations of women because they aren't considered as representations of gender at all. They are just characters. Fictional people with interesting motivations and complex personalities. Sometimes women are reduced to their biological or social roles by the critical feminist, who insists that a character's worth should be evaluated in terms of how successfully she represents women.

Further, I think it's wrong to blame writers or publishers (or Hollywood) for producing male-centred plots for a male demographic. Publishers (and film studios) are, after all, in the business of selling things to people and it's a fact that male audiences are overwhelmingly only willing to pay for masculinised stories, while women will readily consume stories about men or women. This isn't primarily a problem of how women are represented in fiction; it's primarily a problem of masculine identity and insecurity. Fixing this is a large-scale social problem, not something for which we can assign responsibility to publishers and producers.

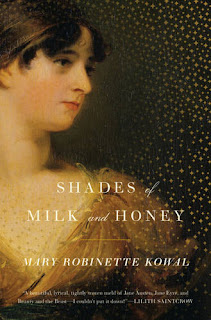

Having said all this, however, I was still disappointed to read Kowal's period romance (which, granted, had an interesting fantasy element) and find that it embodied many Austen tropes and none of Austen's feminism. Kowal has taken elements from each of Austen's novels, including a frustratingly self-centred mother with 'nervous complaints' from Pride and Prejudice; a sometimes-loving, sometimes-tense sister relationship from Sense and Sensibility; and a protagonist whose central motivations are propriety and moral conduct from Mansfield Park.

Jane Austen, in my opinion, ought to be viewed as one of the great feminist writers (some more thoughts on Jane here). Of course, people often complain that her plots revolve around heterosexual romance and reiterate the perceived value of making a 'good match', but Jane Austen did write in 1800. Her heroines move toward the gendered role of wife, true, but she satirises the role of women in society and writes strong characters who demand control of their own futures. These women sparkle; they have opinions and they speak them. In short, we are led to see them as people rather than as women.

Kowal, on the other hand, repeats elements of Austen's comedy (such as women who claim various ailments to garner male attention) without ever ascending to satire. Her main character, Jane, seems to have no motivations of her own other than concerns of morality and propriety, and is frustratingly lacking in personal confidence. The reader is supposed to accept that this inability to assert herself is unproblematically a result of Jane's lack of beauty. While Jane and her sister Melody are given lengthy physical descriptions, the appearance of the male characters is given very little attention. The women are defined by their husband-snaring virtues: Jane's talent and Melody's beauty. Having got to the end of the book, I still don't feel I care for either of them. They aren't characters I care about so much as representations of bland female stereotypes: the talented, plain woman and the beautiful airhead.

I had hoped that Kowal would use her post-feminist outlook to say something more than Austen about the wrongs of treating women as nothing more than candidates for marriage but alas, she manages to say even less.

Re: characters and representing stereotypes. Reading this, I realise that in the fiction I read (which isn't very much :), characters always seem to be Hegelian-like representatives of some philosophical outlook, some psychological archetype, or some social station (Hesse, Huxley, Homer, Kafka). Maybe I'm a bit too far along the autistic spectrum, but I enjoy the idea that human beings are representatives of some perspective (perhaps 'stereotype'?). A lot of pop-culture seems to be just fixation on personality and it can be good to transcend the personal with art, to move from the particular to the universal. This isn't to say that a focus on complex character development, presumably in Austen, is self-absorbed. As i'm sure the perspectives we embody, if any, are not clear cut. David.

ReplyDeleteThat's an interesting idea, and one that I haven't considered before. I don't tend to read such authors, though I certainly have nothing against them. I certainly don't think it's always 'bad literature' to stereotype. Jane Austen herself included many stereotyped characters in her novels, for the purpose of satirizing certain social roles.

ReplyDeleteStereotypes are interesting and helpful if used to examine (as you say) a philosophical outlook or psychological archetype or social role. But I tend to think that stereotypes in themselves aren't interesting. It's what we do with them that's interesting. They become boring and annoying when they are used because they are easy to put into stories, and because the reader will recognise them and their role in the story immediately without having to think about the social norms or philosophical ideas they represent.

Definetely. There are lazy stereotypes and interesting ones (and, like you say in your blog, characters that transcend stereotypes). Having said what I did in my prior post, I think I often like the particular reactions of the characters, as they develop embodying some universal: The peeps of humanity that come out in the realisations that they're performing some function unknown to themselves. Cheers

ReplyDelete